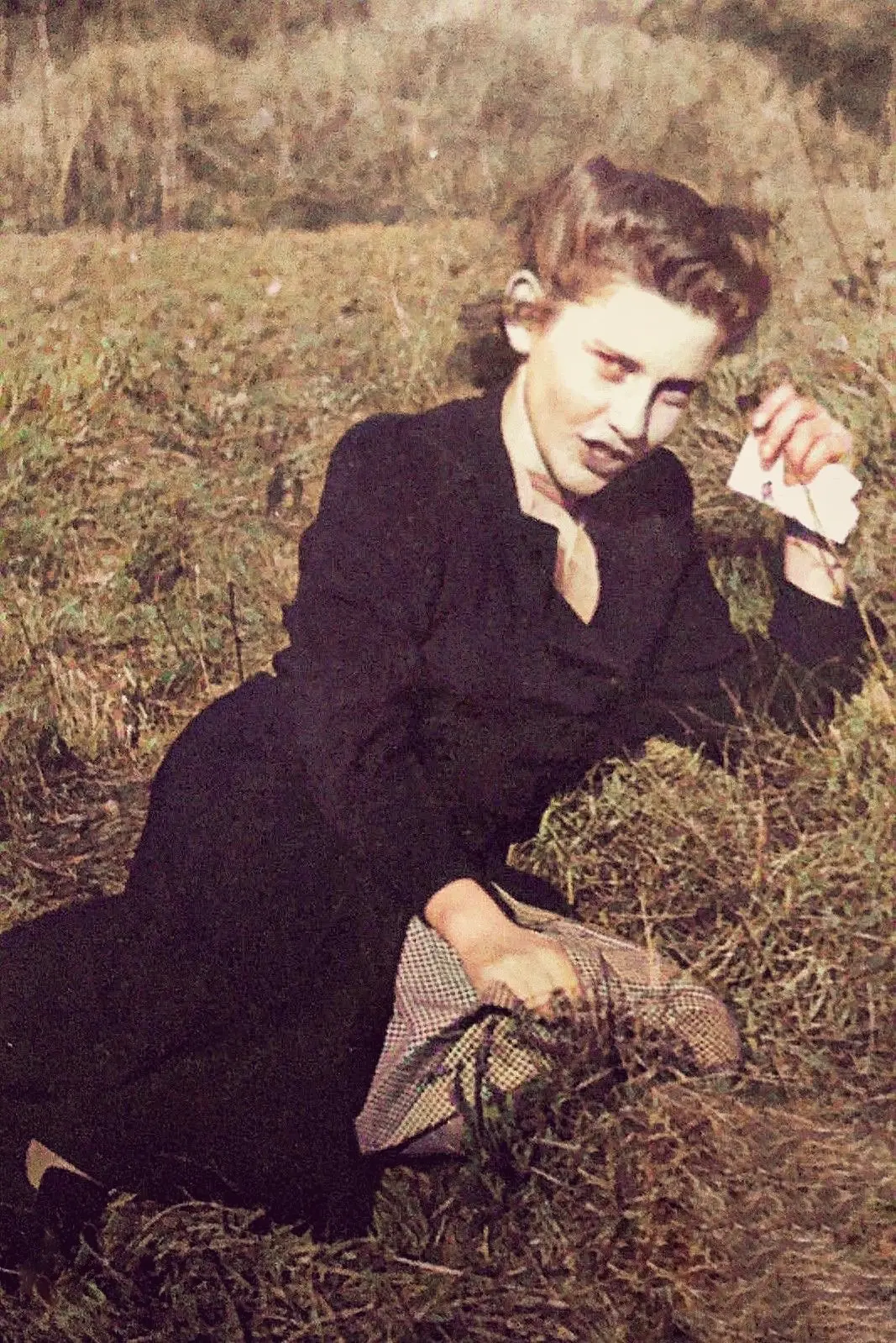

She has won the Grimme Award, the German Acting Award, the Nestroy Theater Award twice, and has been chosen as Actress of the Year just as often - Caroline Peters is a superstar of German acting and shines on the stage of the Vienna Burgtheater just as she does on television or on the big screen.

Like no other, she embodies the tragedy of Clytemnestra just as convincingly as the quirky inspector Sophie Haas in Murder with a Viewor the frustrated mother in Sönke Wortmann's blockbuster The First Name. What she touches turns into a ratings hit. And yet the choice Viennese has remained approachable, incredibly funny, down-to-earth, and always open to new challenges.

Caroline Peters has just written her first novel: Another LifeNot a biography, but an autofiction, based on her own life story and that of her mother, which she tells with great empathy and a lot of humor.

What is the first thing that comes to your mind when you think of the word 'we' in connection with your family?

Me and my siblings. And then there are the parents. But they are the others. And I find that somehow ridiculous. Thinking like that as a child or teenager is understandable. The parents really are the others, the ones who tell you when to go to bed, who drive the car, and who have the money.

At some point, it must be possible to approach your parents on equal footing.

But why do we still think like that as adults? At some point, it must be possible to approach your parents on equal footing. Instead, most people remain stuck in these rigid family role patterns: the father, the mother, the child.

I find that unbelievably stiff and boring. The person or rather the personality behind it is not noticed at all. Why should you even meet then? Just to confirm old clichés or accusations once again?

I think that's how it goes for most people, that they become children again as soon as they cross the threshold of their parents' house.

And I want to break this view in my book. The first-person narrator tries to encounter her mother like an adult, like a friend. A woman who was once young herself, had ambitions, and fell in love. Moving away from this societal code, in which a mother always owes her child something - namely total self-sacrifice, complete devotion, and endless attention. When were these clichés of the perfect mother actually imposed on our personal relationships?

One sits across from each other in one's own kitchen and instead of talking to an interesting woman, one talks as a daughter with a kind of service worker whom one believes is responsible for one around the clock and responsible for all our botched lives. I find that tragic and wasted love. Because only when we realize that we all make mistakes, we are truly free.